The definition of homelessness is “the state of having no home”. It is estimated that 150 million people around the globe face homelessness, with 1.6 billion people lacking safe or adequate housing.

There are 3 “types” of homelessness:

Refers to those who reside in emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, or safe-havens.

Refers to those who reside in places not designated for living or sleeping; such as streets, vehicles, or parks.

Refers to people with a disability who have been continuously homeless for a year or more, or who have been homeless at least 4 times in the past 3 years (amounting to at least 12 months).

Regardless of the nature of homelessness, being homeless wreaks havoc on the individual's health; physically, mentally, and emotionally. Some people face homelessness as a result of mental and physical health issues, which worsen when forced into homelessness. Others find that homelessness is the catalyst for mental and physical health challenges.

Being homeless is not a crime, yet homelessness is often criminalized. This drives homeless people even further into the shadows, exacerbating their mental and physical challenges.

In January of 2020, there were 580,466 people in America facing homelessness. Seventy percent of those were individuals, while the rest were families living with children. These numbers came out before the pandemic – before businesses were shuttered and countless Americans lost their incomes and economic security.

Because of Covid related concerns, there will be disruptions in the accounting of homelessness until 2022, or early 2023.

People with disabilities account for 19% of “chronic homeless” people, those who have been homeless for a year or more, or have been homeless at least 4 times in the past 3 years.

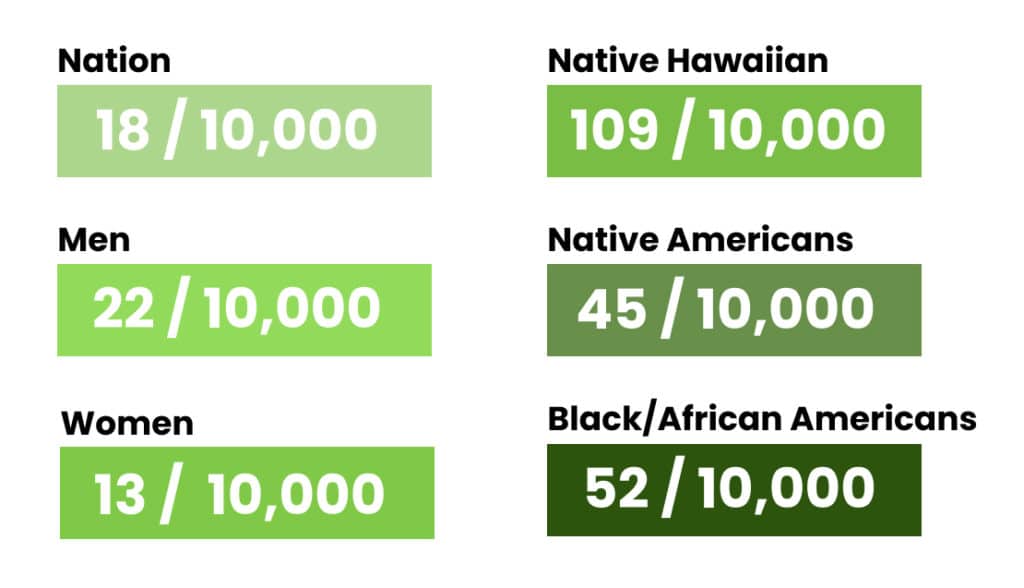

Males are almost twice as likely to experience homelessness than females. Out of 10,000 males, 22 are homeless; for women, it’s 13. Seventy percent of homeless individuals are men.

While the numbers show white people to be the most prominent racial group to experience homelessness, marginalized racial groups are much more likely to face segregation and discrimination in the employment and housing markets, and consequently homelessness as well.

The nation's overall rate of homelessness is 18 out of every 10,000. However, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders have 109 out of 10,000; Native Americans have 45 out of 10,000; Black or African Americans have 52 out of 10,000.

While the numbers show white people to be the most prominent racial group to experience homelessness, marginalized racial groups are much more likely to face segregation and discrimination in the employment and housing markets, and consequently homelessness as well.

The number of homeless veterans has decreased by 39% since 2007. Homeless families (with children) have decreased by 27% in that same time frame. Chronic individual homelessness had dropped by 35% (again, these numbers are pre-pandemic).

These decreases show that homelessness can and has been reduced when the issue is prioritized by the nation, state, and local governments.

The number of homeless veterans has decreased by 39% since 2007. Homeless families (with children) have decreased by 27% in that same time frame. Chronic individual homelessness had dropped by 35% (again, these numbers are pre-pandemic).

In actuality, homelessness is just one missed housing payment, one broken leg, one relapse, or one mental health crisis away for many, many people. Here are some of the causes of homelessness in America:

We are in the midst of one of the most severe affordable housing crises in history. Eight million low-income households pay more than half of their incomes towards housing, making them incredibly vulnerable to housing instability and homelessness.

Rents continue to rise, while wages remain stagnant. The supply of affordable housing continues to diminish. It is tough for individuals or families to “better their circumstances” through education and new careers while they are living hand to mouth just to survive.

A challenging labor market, limited education, gaps in work history, criminal records, lack of transportation, unstable housing, poor health, and disabilities are all factors that contribute to one's lack of ability to obtain and retain stable and reliable income

Wages have been stagnant for the past 3 decades, while the price of housing has continued to increase. This leaves an ever-growing percentage of our population in danger of homelessness.

For many people, domestic violence is the cause of their homelessness. Survivors of domestic violence may turn to homeless shelters seeking temporary refuge after fleeing a violent situation at home. Others may seek out those programs because they lack the financial resources needed for housing after leaving an abusive relationship

On one night in 2019, there were 48,000 shelter beds set aside for survivors of domestic violence.

African Americans and Indigenous people experience higher rates of homelessness than white people. African Americans account for 13% of the general population, but 39% of homelessness and 50% of homelessness in families.

Poverty is a predictor in homelessness, and Black and Latinx groups are grossly overrepresented in poverty levels in comparison to their representation in the general population.

Physical and mental illnesses, as well as long-term disabilities, may lead to homelessness as a result of not being able to work or function. One may become chronically homeless when that health condition becomes disabling. The state of homelessness will likely exacerbate the illness, worsening the condition that led to homelessness in the first place.

People living in shelters are almost twice as likely to have a disability compared to the general population. Diabetes, heart disease and HIV/AIDS are often 3-6 times more prevalent in homeless people than in the general population.

People with mental health or substance abuse issues who are homeless have a higher likelihood of living with immediate, life-threatening physical illnesses.

The number of opioid-related overdose deaths has tripled since 2020. While those of every socioeconomic and racial class are affected by this opioid epidemic, homeless people are disproportionately impacted.

More than 10% of people who seek out substance abuse or mental health treatment are homeless.

The number of homeless veterans has decreased by 39% since 2007. Homeless families (with children) have decreased by 27% in that same time frame. Chronic individual homelessness had dropped by 35% (again, these numbers are pre-pandemic).

Homelessness tends to be separated into 2 categories: “mentally ill homeless” and “non-mentally ill” homeless. This is dangerous and outdated thinking as it creates the mentality that the non-mentally ill homeless person is more deserving of help and resources than the mentally ill homeless person.

Homelessness is a huge struggle, psychologically and emotionally. The combination of unsafe sleeping conditions, isolation, lack of support, poor diet, and psychological deprivation can greatly exacerbate pre-existing mental health issues for those who have them and can lead to mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders for those who previously did not.

The connection between homelessness and mental illness is complicated; it’s a two-way relationship, and not necessarily directly correlated.

Treating homeless people with mental health issues presents unique challenges. Many people facing homelessness have co-occurring disorders, such as depression on top of substance abuse disorders. It can be difficult to prioritize which disorder to treat first, especially when the person doesn’t have a safe place to live, and to allow healing to occur.

Homeless individuals are often dealing with trauma; which may have occurred in the past or as a result of being homeless, or both. 68% of men and 76% of homeless women report experiencing a traumatic event at some point in their past.

People experiencing homelessness on top of substance abuse disorders have a high risk of overdose as a result of substance abuse, making treatment even more important, and also more difficult.

In the early 2000’s the “Housing First” philosophy was widely recognized and used by many federal, state, and local government agencies as the model for treating the homeless population. The idea was to provide shelter, as well as medical, mental, and substance abuse treatment via case managers and multidisciplinary teams.

Unfortunately, without adherence and compliance to these programs by the homeless population these programs don’t appear to work in the long term. The more current approach is that a trauma-informed approach is necessary in order to address the heart of the problem that led to homelessness.

Homelessness is often a symptom of a bigger problem. Just as with depression, anxiety, and substance abuse, one needs to address the root of the problem in order to overcome it. Providing shelter to a homeless person will only go so far if they’re still unable to stay sober, hold down a job, or address their health issues.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) recommends the following model for treatment of substance use disorder amongst the homeless population. It is a good guide towards understanding the priorities and complexities in treating this demographic.

Homelessness is a global issue, as well as a community issue. Services can be targeted universally (entire communities), selectively (at-risk subsets of the population), or indicatively (individuals). It’s tricky; we see “homelessness” as this broad category that everyone fits into, but it’s just not that simple. Every homeless individual has their own story, their own history, and their own unique challenges to overcome.

The first step in treating addicted homeless people is to see where they’re at. Are they in immediate danger? Will they need to be medically detoxed? Are they suffering from untreated trauma? It’s important to get a full history of any medical or mental health issues, as well as to learn the story of their current homelessness.

For a person without a home, addressing issues such as health care, finances, criminal history, not to mention housing, can be overwhelming if not impossible. That’s why it’s so important to meet each individual where they’re at, and to set attainable goals towards sobriety and a sustainable living situation.

Goals need to be realistic and set as a team. Milestones should be rewarded in order to maintain compliance. People in this situation are often beaten down and defeated; every little step towards health and wellness is a huge step, and should be recognized

Recovery is a life-long process. People with comorbid disorders (addiction plus mental health issues) face a higher risk of relapse, and homelessness compounds that risk. In order to succeed and overcome these various obstacles the following strategies are used:

Wellness and Illness self-management:

The client learns to manage their health and wellness, and acquires tools for doing so on their own for the long term.

Assertive community treatment:

The client receives integrative community-based services. The more people involved in the individual's care, the more likely they will succeed in treatment. Different people have different needs; it often takes a village to meet those needs.

Motivational Interviewing:

This is a counseling approach focused on guiding the client towards the motivation to make positive choices and decisions in the future.

Achieving and maintaining sobriety takes an incredible amount of courage, strength, and determination. Doing so while homeless is even more challenging. There has been progress towards lessening the stigma attached to addiction. More people are speaking openly about their struggles, and the general public is starting to understand that addiction is a disease and not a moral failing or a sign of weakness.

The stigma still exists though, and homelessness is definitely still stigmatized. Discrimination towards the addicted homeless population is rampant. The more we understand the more we can help individuals find their way back towards wholeness.

COVID-19 presented serious challenges to those already experiencing homelessness, as well as to those who were on the verge of being so. The economic fallout of mass businesses being shut down (many of them permanently) will be felt for years.

The crisis did shine some much-needed light on the struggles homeless people face on a daily basis, as well as on the huge population of people who are just one missed paycheck away from being homeless themselves.

At the same time that people were losing their jobs, and therefore their homes, homeless shelters were forced to limit the number of people they could offer beds to for fear of spreading the virus – many of those shelters have been forced to close their doors for good.

The silver lining is the increased attention and focus on these issues that have existed for decades, and yet were pushed to the background. COVID-19 pushed these issues straight into the limelight.

People need to be housed, yes. But they also need the support necessary to stay housed. Individuals need access to services; health services, mental health services, and legal aid services. Without continuing support and education, the circumstances that led to homelessness in the first place will just continue to exist.

There has been a reduction in homelessness among veterans in the past several years, as well as amongst homeless families. This means that there are solutions to homelessness that work. And we’re starting to better understand what works and what doesn’t.

While the pandemic was catastrophic for many homeless people (including the newly homeless as a result of the pandemic), it also prompted advocacy efforts that secured billions of dollars in federal resources to help people who are homeless, or close to it.

With coordination, assistance for the most vulnerable, and an effective crisis response system homelessness can be drastically reduced and even eradicated.

State of Homelessness: 2021 Edition. (2021, August 16). National Alliance to End Homelessness. https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness-2021/

Health and Homelessness. (2021). The American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/homelessness-health

Definitions of Homelessness. (2021). SAMHSA SOAR TA Center. https://soarworks.samhsa.gov/article/definitions-homelessness

Definition of Homeless. (2021). California Department of Education. https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/hs/homelessdef.asp

Homelessness and Racial Disparities. (2021, April 1). National Alliance to End Homelessness. https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/what-causes-homelessness/inequality/

About Homelessness | Mental Health. (2021). The Homeless Hub. https://www.homelesshub.ca/about-homelessness/topics/mental-health

Homelessness & Health: What’s the Connection? (2021). National healthcare For The Homeless Council. https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/homelessness-and-health.pdf

Behavioral Health Services For People Who Are Homeless. (2021). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/PEP20-06-04-003.pdf

Tranum, S. (2021, November 4). What if we treat homelessness like a pandemic? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/what-if-we-treat-homelessness-like-a-pandemic-168553